6. Scope of ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’¶

6.1. Generic considerations¶

In order to analyse the balance between broader possible openness and the necessity of closing some scientific results, it is relevant to start from some classical works out of the temporary scope of this literature review, which are cornerstones of our occidental culture. If classic Greece showed that knowledge is transmissible through education and virtues through habits, the Enlightenment demonstrated a special focus on knowledge as the Encyclopédie evidenced. Kant distinguishes in his Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung (Kant, 1999 [1784]) two uses of reason: public and private. Public use of reason must always be free and is the only one that can enlighten. Public use of reason, he states, is the one practised by a scholar before the reading public. Kant's text belongs to a tradition of understanding citizens as moral agents, owners of autonomy, which is basic for a democratic régime. In the same tradition, Karl Popper's The Open Society and its enemies [1945] is a deep defence of democracy and its values. He asserts in this work that 'what we call 'scientific objectivity' is not a product of the individual scientist's impartiality, but a product of the social or public character of scientific method; and the individual scientist's impartiality is, so far as it exists, not the source but rather the result of this socially or institutionally organized objectivity of science. Any assumption can, in principle, be criticized. And that anybody may criticize constitutes scientific objectivity' (Popper et al., 2013, pp. 426-427). But what is most important from Popper, in the tension open-close, is the theory of falsifiability contained in his The Logic of Scientific Discovery [1935]:

'Theories are, therefore, never empirically verifiable [...] But I shall certainly admit a system as empirical or scientific only if it is capable of being tested by experience. These considerations suggest that not the verifiability but the falsifiability of a system is to be taken as a criterion of demarcation. In other words: I shall not require of a scientific system that it shall be capable of being singled out, once and for all, in a positive sense; but I shall require that its logical form shall be such that it can be singled out, by means of empirical tests, in a negative sense: it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience.' (Popper, 2002, p. 18).

The immediate conclusion after Popper's ideas is that only a system where falsifiability is possible would be an objective scientific one. Modern science should be a synonym for public and transparent science, 'a process of community and scattered construction of knowledge that unfolds in different forms of communication' (Caso, 2020). Scientific objectivity is therefore only possible 'where there is free and open communication of the results of research' (Eamon, 1986, p. 321).

In the literature review, few studies have been found that address a study of the expression as 'open as possible, as closed as necessary', referred to Open Science and when it is tackled they only occasionally refer to the reusability of the data and their licenses (Labastida & Margoni, 2020). It is much more common that this expression drives to the accessibility of the data due to another legal issue, the privacy, instead of the copyright (Landi et al., 2020). The statement 'as open as possible, as closed as necessary', overcited and beautifully phrased, is very difficult to pin down in practice. It became the principle to define the balance needed between openness and protection of scientific information, particularly in the context of research data. This principle has become popular in the recommendations of Research Data Management (RDM) in Horizon 2020. It was first established as part of the specifications of the ORD (Open Research Data) pilot in the rules for 20161 and then extended to all Horizon 2020 projects2. The ORD pilot aimed to improve and maximise access to and re-use of research data generated in EC funded projects, and explicitly took 'into account the need to balance openness and protection of scientific information, commercialisation and Intellectual Property Rights, privacy concerns, and security, following the principle "as open as possible, as closed as necessary"'(J.-C. Burgelman et al., 2019, p. 3).

The expression is contained in paragraph 10 of UNESCO's (2021) Draft Recommendations, that includes two types of limitations, first referring to the nature of the information and second regarding its ownership. This paragraph draws the boundaries between 'open' and 'closed', taking sides in favour of openness but allowing exceptions:

'Scientific outputs should be as open as possible, and only as closed as necessary. Open Science affords necessary protection for sensitive data, information, sources, and subjects of study. Proportionate access restrictions are justifiable on the basis of national security, confidentiality, privacy and respect for subjects of study. This includes legal process and public order, trade secrets, intellectual property rights, personal information and the protection of human subjects, of sacred indigenous knowledge, and of rare, threatened or endangered species. Some research results, data or code that is not opened may nonetheless be made accessible to specific users according to defined access criteria made by local, national or regional pertinent governing instances. The need for restrictions may also change over time, allowing the data to be made accessible at a later point'.

This expression has become commonplace and it would be useful to analyse it through the interpretation of the four ambiguous terms 'open', 'close', 'possibility' and 'necessity' that it contains. Using a document as an example, the possibilities of using the information contained therein are the following ones, from less to more:

-

The document's existence is unknown.

-

The document's existence is known but its container cannot be physically accessed. Example: the container of the files with US nuclear weapon codes.

-

The document's existence is known, its container can be physically accessed but the content cannot be accessed. Example: an 8 inch floppy disk.

-

The document's existence is known, its container can be physically accessed, the content can be accessed but the content cannot be understood. Examples: enciphered document, binary code.

-

The document's existence is known, its container can be physically accessed, the content can be accessed, the content can be understood but the content may not be legally used due to its nature. Example: personal data, blasphemy, defamation, national security, pedophile content...

-

The document's existence is known, its container can be physically accessed, the content can be accessed, the content can be understood, the content can be legally used due to its nature but the content may not be legally used due to IP laws. Examples: a book, source code.

-

The document's existence is known, its container can be physically accessed, the content can be accessed, the content can be understood, the content may be legally used due to its nature and the content may be legally used according to IP. Example: a book under a Creative Commons By license.

Therefore, a spectrum exists from 'close' to 'open' which depends on different parameters (see Table 11) such as knowing that the information exists, the physical access to the container and to the content, being able to understand the code in which the content is written and finally, its usage conditions. 'Close' and 'open' are not two opposed states of the same binary reality, but a status that accepts different grades of openness.

| Parameter | Type of parameter |

|---|---|

| Knowing the information exists | Epistemological |

| Access to the container of the information | Physical |

| Access to the content | Physical |

| Understanding the content | Epistemological/legal3 |

| Content limited by the nature of the information | Legal |

| Content limited by ownership | Legal |

Table 11. Parameters of access and usage of information

Due to the focus of this report, neither the epistemological nor the physical parameters will be studied. Regarding the epistemological issues, the cognitive success as a prius for Open Science is subject matter of philosophical studies, while the physical hindrances are studied under the topic of interoperability, where both hardware and software will be the keys that make possible the access, use and reuse of the information. This literature review is oriented to the analysis of the legal conditions, where two types of limitations of 'openness' can be found: the first one is related to the nature of the information, and the second to the ownership of such information. While the first limitation refers to the content of the message, the second refers to its owner.

6.2. As open as possible based on the nature of the information¶

Regarding the nature of the information as a legitimate cause to limit its public availability, it is a cause that already exists and is accepted in democratic regimes. When it comes to information circulation, modern democracies are based on the existence of default rules, which are freedom of thought, freedom of press, freedom of information and freedom of expression. All information is allowed by default to become public, except when applying certain limits rooted on the tension with other rights that deserve equal or similar protection. UNESCO's Draft Recommendation is aware of this regulation and mentions the exceptions of 'legal process and public order, [...] personal information and the protection of human subjects, of sacred indigenous knowledge, and of rare, threatened or endangered species'. International courts justify these limits based on the nature of the information and have granted protection, among other rights, to restrictions on the access and reuse of information due to national security4, privacy5 6, blasphemy7, reputation8, hate speech9, right to oblivion10 and access to the documents of the institutions based on privacy11. Some of these limitations are based on legal concepts with clear boundaries, for example, there is a strict personal data regulation, but other terms such as national security are subject to interpretation. Also, criminal codes have strict regulations that include conducts where disclosure or dissemination of information constitutes a crime. All these cases may constitute legitimate reasons that limit the possibility of the access, use and reuse of scientific information and therefore allow to draw the boundaries of the expression 'as open as possible, as closed as necessary'. These limits can be imposed by a state in the exercise of their sovereignty and the discussion about their existence and enforceability should be held in tune as to which ones are acceptable in a democratic society where, as seen, freedom of information is the default rule.

Furthermore, as UNESCO's Paragraph 10 explicitly establishes, these generic limits based on the nature of the information may be raised in specific cases: 'Some research results, data or code that is not opened may nonetheless be made accessible to specific users according to defined access criteria made by local, national or regional pertinent governing instances'.

The summary of this subsection is that the expression 'as open as possible, as closed as necessary' can be interpreted therefore in the sense that a governing instance may impose conditions to the openness based on reasons acceptable in a democratic society and, simultaneously, regulate exceptions to the limiting conditions. The necessity to close the information would be based in laws that forbid the access, use and reuse of the information due solely to the nature of its content.

6.3. As open as possible based on the ownership of the information¶

Regarding limitations based on the ownership of the information, UNESCO's mentioned text literally includes 'trade secrets' and 'intellectual property rights'.12 In this context, notwithstanding the scarcity of the analysis of the expression 'as open as possible as close as necessary' in scholar publications, a vivid discussion on what is to be considered 'open' in regard to IP was held in the FOSS communities can help to delimit the scope. The most recent outcome of this debate was the 'Open Definition' due to the efforts of the Open Knowledge Foundation:

'The Open Definition sets out principles that define "openness" in relation to data and content.

It makes precise the meaning of "open" in the terms "open data" and "open content" and thereby ensures quality and encourages compatibility between different pools of open material.

It can be summed up in the statement that:

"Open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness)."

Put most succinctly:

"Open data and content can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone for any purpose"'13.

The discussion held under the shelter of the Open Knowledge Foundation was the heir of the debates that confronted the FSF and the Open Source movement during the 80's of the XX century. The 'Open Definition' web page narrates its historical background with the following words:

'The Open Definition was initially derived from the Open Source Definition, which in turn was derived from the original Debian Free Software Guidelines, and the Debian Social Contract of which they are a part, which were created by Bruce Perens and the Debian Developers. Bruce later used the same text in creating the Open Source Definition. This definition is substantially derivative of those documents and retains their essential principles. Richard Stallman was the first to push the ideals of software freedom which we continue.'14

As explained in Subsection 5.1.3. Free software, even though the two groups FSF and Open Source had a different position regarding the possibilities of the author of a derivative work to close it (the GPL license obliged the derivative code, if distributed, to remain accessible, on the contrary to the Open Source group), both groups agreed on the importance of the legal permission to read and to modify the source code of a primary work, and to distribute it jointly with the derivative work. The definition supported by the Open Knowledge Foundation follows the thesis of the necessity for the derivative work to remain open. Therefore, it follows the obligation that the openness must be virally transmitted between the original and its subsequent derivative works. To be 'open' means that the primary work is licensed in such a way that it allows the creation of derivative works using it, that consequently these derivative works are licensed in such a way that they allow further derivative works and so on.

But the history of the term 'open' cannot be understood without a reference to the term 'free'. The reference made in the Open Definition to 'free' ('Open data and content can be freely used, modified, and shared by anyone for any purpose') continues the FSF tradition regarding the concept of 'freedom' in its application to source code works. This organisation explains that free 'is a matter of liberty, not price. To understand the concept, you should think of "free" as in "free speech," not as in "free beer"'15. This liberty is given by the author of the original work not only to future creators of derivative works but also to the users in general, so they may control the software instead of the software controlling them. It is composed by four elements:16

-

'The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0)'.

-

'The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this'.

-

'The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others (freedom 2)'.

-

'The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this'.

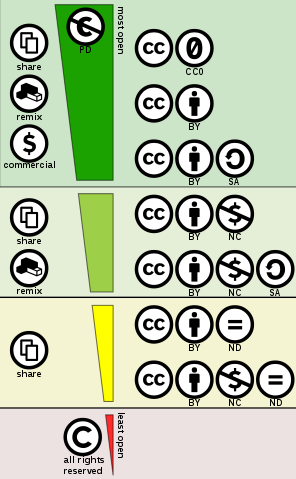

Thus, both terms 'open' and 'free' can be interpreted as synonyms, being their antonym the term 'closed.' This interpretation is found in the Creative Commons website licenses page. When choosing one license for a work,17 the web page displays the message "This is a Free Culture Licence" for the licenses 'CC By' and 'CC By ShareAlike' and the message 'This is not a Free Culture Licence' for the licenses 'CC By Attribution No Derivatives', 'CC By Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives' and 'CC By Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike'.

Both messages link to an explanation of the organisation Creative Commons of what are considered 'Free Cultural Works'.18 Creative Commons organisation understands that a 'cultural work' is considered 'free' if it allows four possibilities: (1) to use the work itself for any kind of use (reason why non commercial licenses are not considered 'free'); (2) 'Freedom to use the information in the work for any purpose'; (3) 'Freedom to share copies of the work for any purpose' and (4) 'Freedom to make and share remixes and other derivatives for any purpose' (reason why no derivative licensed works are not considered 'free'). That the terms 'open' and 'free' operate as synonyms is supported also by the image contained in this webpage. The image Creative Commons License Spectrum (Fig. 7) draws a gradient between "most open" and "least open". It uses the term 'open', not the term 'free'.

Fig. 7. 'Creative Commons License Spectrum' by Shaddim (CC BY).

But although the discussion about 'free' and 'open' has been rich in the FOSS and Creative Commons communities, its context was kept in the field of copyright, not within the other main fields of IPR (patents, trademarks or trade secrets) where the literature review shows no results. Patents must publicly disclose the information of the invention, therefore finally they should not hinder the transmission of knowledge, although the possibility to keep the patent application secret temporarily; trademarks do not close any information and, under a logical point of view, trade secrets are the paradigm of a closed information.

In the previous subsection it was stated that the limitations to the openness of the information based on the nature of the content could be imposed by the normal limitations that exist in a democratic regime, and the exception to the limitations could be decided, using UNESCO's words, 'by local, national or regional pertinent governing instances'. But when the scope of the expression 'as open as possible, as closed as necessary' is analysed under IP norms, then the decisions to close scientific knowledge on publicly funded projects should be analysed, scrutinized, rejected by default and only accepted if a closed catalogue of reasonable conditions is met. It is true, as CODATA submitted to the UNESCO Open Science Consultation (CODATA Coordinated Expert Group et al., 2020) that Open Science 'categorically does not mean indiscriminate openness', but the default rule is that any closed reason should be made evident and that the limits based on the nature of the information already serve as a reasonable scenario. Going beyond these limits should need a good reason, as it is legitimate that projects funded by the taxpayers should return the results to the society in general.

In privately funded projects, the freedom of establishment must be held. Therefore, it would be the funding body who should decide on the openness of the outcomes of the research activity. Nevertheless, a lesson learnt from Rachel Carlson's Silent Spring (1994) is that what private companies may do with private money can affect our environment and our health. It must be clear that risks to humans must be communicated to the public 'or to those whose job is to implement and enforce precautionary measures'19. Simultaneously, the public must have the right to enquire and receive information on these activities20.

-

https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/oa_pilot/h2020-hi-oa-data-mgt_en.pdf ↩

-

The ORD pilot was extended from 2017 to all Horizon 2020 projects as it could be seen in the Annotated Grant Agreement (2019): https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/amga/h2020-amga_en.pdf#page=243 ↩

-

The epistemological impossibility may be caused through the usage of digital rights management that enciphers the content. ↩

-

See Commission Decision (EU, Euratom) 2015/444 of 13 March 2015 on the security rules for protecting EU classified information http://data.europa.eu/eli/dec/2015/444/oj ↩

-

Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) 8 April 2014, Joined Cases C‑293/12 and C‑594/12, Digital Rights Ireland Ltd (C‑293/12) v Minister for Communications, Marine and Natural Resources, Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Commissioner of the Garda Síochána, Ireland, The Attorney General, intervener: Irish Human Rights Commission, and Kärntner Landesregierung (C‑594/12), Michael Seitlinger, Christof Tschohl and others. ↩

-

Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) 6 October 2015 Case C‑362/14, Maximillian Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner, joined party: Digital Rights Ireland Ltd. ↩

-

Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights 20 September 1994, Case of Otto-Preminger-Institut v Austria. ↩

-

Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights 30 March 2010, Case Petrenco v the Republic of Moldova. ↩

-

Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights of 23 September 1994, Case jersild v Denmark. ↩

-

Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) 13 May 2014, Case C‑131/12 Google Spain SL, Google Inc. v Agencia Española de Protección de Datos (AEPD), Mario Costeja González ↩

-

Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber) 29 June 2010, Case-28/08, European Commission, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Council of the European Union v The Bavarian Lager Co. Ltd, Kingdom of Denmark, Republic of Finland, Kingdom of Sweden. ↩

-

Even though trade secrets is one of the fields of intellectual property. ↩

-

The form is available at https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/ ↩

-

See https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/public-domain/freeworks ↩

-

See 'The BSE (Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy) Enquiry Executive Summary', p. xviii https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20060525120000/http://www.bseinquiry.gov.uk/pdf/volume1/ExecSummary.pdf ↩

-

In its judgement of 19 February of 1998, in case of Guerra and others v Italy, the European Court of Human Rights declared that Italy had violated Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights: '60. The Court reiterates that severe environmental pollution may affect individuals' well-being and prevent them from enjoying their homes in such a way as to affect their private and family life adversely'. ↩