4. Intellectual property¶

There is a traditional discussion about the legal nature of the rights regulated by intellectual property norms due to the intangible condition of the objects ruled under this legislation. For the purpose of this report, this discussion is not relevant, since we start from a notorious fact: the law considers that information that accomplishes certain characteristics is subject to what has been traditionally understood as 'protection' and enforces a proceeding to cease any activity held over the said information and to indemnify its rightholder. What is relevant for this study is the existence of a legal regulation whose object is information and that, in order to exercise certain activities over such information, the consent of the rightsholder is needed, with the sole exceptions included in the law, if any, and no others. Therefore a general rule is applicable: if there is no consent from the rightholder or there is no legal provision, nobody may exercise certain activities defined in the law over certain information; hence a monopoly is created. Intellectual property legislation creates a sphere where all activities over an item are forbidden by default unless one or more of these conditions are met: (1) Consent from the rightholder; (2) The use of the information according to a specific legal permission (a limitation of copyright, a suspension of a patent) which is always interpreted restrictively; and (3) the right of the owner expired due to the passage of time. This context of forbidden by default, as we will describe below, is a legal burden to the free transmission of information. The expression 'all rights reserved' is applicable even when nothing is stated.

The term Intellectual Property comprises four major different fields: copyright, patents, trade marks, and trade secrets (Anderfelt, 1971; Bainbridge, 2012; Bouchoux, 2013; Kur & Dreier, 2013; McJohn, 2021; Sinnreich, Aram, 2019; Vaidhyanathan, 2017; WIPO, 2008). Copyright applies to original works of authorship as soon as they are fixed in any tangible medium of expression. Patents consist in the invention of a process or a product. Trademarks refer to a symbol used in commerce to identify the original producer of goods or services so as to distinguish them from other products in the market. Trade secrets consist of information that is valuable because it is not generally known.

Although most literature only mentions these four categories as the intellectual Property components, other rights have been included under this term, such as designs, plant varieties, domain names, geographic marks (Blakeney, 2014), personality rights, industrial designs and integrated circuits, fashion and traditional knowledge (Vaidhyanathan, 2017; Dreyfuss & Pila, 2018), confidentiality, and computer technology (Torremans, 2013). According to some authors, this concept should only include 'rights that are related to some kind of effort or achievement and not to a person's personality or personal characteristics' (Rognstad, 2018, p. 8). Thus, the common characteristic to all categories would be the creation of a work through intellectual efforts over a common good.

4.1. Historical background and justification¶

Traditionally, IPR have been divided into two types: artistic and industrial intellectual property. Artistic IP would refer to copyright, and industrial IP would comprise patents and trademarks. In order to understand current IPR regulation, it is important to realise the different paths through which the two types came to be protected under it.

Although the 'earliest genuine anticipations of copyright were the printing privileges' (Rose, 2002) our modern system is the result of the confluence of English and French regulations. The first came via the enactment by the British Parliament in 1710 of the Statute of Anne, although some authors consider that this statute 'was neither the first copyright act in England, nor was it intended primarily to benefit authors. It was a trade-regulation [...] to prevent a continuation of the booksellers' monopoly' (Patterson, 1968). The second came with the dissemination of Enlightenment ideas at the end of the eighteenth century in France, influenced by the spirit of individualism that characterized the passing of the Ancien Régime to a new one, and brought a new perspective related to the personality of the author. Using Susan Sell's words to describe both contributions, there was a tension 'between romantic notions of authorship and invention on the one hand, and utilitarian conceptions of incentives for creation and diffusion on the other' (2004). The romantic notions of creation were attached to the doctrine of natural rights and the work was thus 'private, subjective, expressive, and perpetual'. On the contrary, the utilitarian theory was more focused on the dissemination of the work to the public, the objective nature of knowledge, and a limited extension of the rights.

Several authors have justified intellectual property on works produced with an intellectual effort. The groundings of their justification use theories from John Locke, Hegel, the utilitarians Bentham and Mill (Spinello & Bottis, 2009, pp. 149-172) and Kant (Merges, 2011). Using John Locke's theories, the justification for property is built on the legitimacy that a person obtains when appropriating herself from a work exercised using common goods. A person who fishes or harvests is allowed to appropriate the result, thus beginning a cycle where the original owner may endorse her rights over this object to another person. The Lockean expression of the 'sweat of the brow' exercised over a good accessible to all would legitimize the appropriation of the result of the effort of who would be the original author (Spinello & Bottis, 2009). The legitimacy of the second owner is built over the legality of her agreement with the first and so on. Apropos Hegel, 'Hegel espouses the principle that property is a natural right with intrinsic value because it provides freedom for the self, which, through the exercise of that freedom, objectifies itself in the external world, that is, gives its personality a reality outside itself' (Spinello & Bottis, 2009, p. 166). A utilitarian foundation would be based on the presumption that 'the development of scientific, literary and artistic works will promote general utility or social welfare' (Spinello & Bottis, 2009, p. 168) and finally, regarding the justification based on Kant, his theories about property do not have empirical or factual groundings but rather are based on abstract concepts such as the need for humans to control objects in order to act and obtain the results they intend. In order to achieve this, they need some enforcement over the things they use, which necessitates a strong legal system. This, as Merges puts it, is only possible with a government and a civil society. Therefore, 'it could be said that for Kant property [...] lies at the heart nothing less than civilization' (Merges, 2011, p. 73) .

A similar approach is made by Ole-Andreas Rognstad (2018, pp. 13-41), who distinguishes four categories of justification: (1) utilitarianism, (2) the labour idea, (3) personality ideas, and (4) other ideas. The utilitarian approach is rooted in Jeremy Bentham's utilitarian moral philosophy and it would justify property using Bentham's 'principle of utility'. The labour idea follows Locke's theories. The personality justification would be based in Kant and Hegel's thoughts, due to the capacity of persons to be autonomous entities, from which it derives the possibility (or necessity) of holding rights. Rognstad's fourth category of intellectual property justification is based on different authors such as Aristotle and his eudaimonia ultimate end of human life, and the continuation of this approach under moral principles.

4.2. Stages of IPR legal regulation¶

Since their inception, IPR have been the object of a globalisation effort to harmonize their content and enforceability. We could summarize the different phases in three stages. The first began with the legal recognition of IPR and lasted until 1886, the year of the signing of the Berne Convention. The second stage would be from the Berne Convention to the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement (TRIPS) and the third would cover the period from TRIPS Agreement until today (Olwan, 2013, p. 36).

In their initial conceptualization, IPR were legally recognized and enforceable in the national state of the author or, in the case of copyright, in the country the book was first published. The doctrines of IPR justification were, during this stage, based more on utilitarian than natural theories, which implied a local and not universal vision. This initial system was criticised by some authors, the best known complaints being those made by Mark Twain against Canadian and English publishers who used his works without permission (Courtney, 2017; Vaidhyanathan, 2001). As studied by Carla Hesse, due to this local regulation 'the first great publishing houses in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston built fantastic fortunes on unauthorized, and unremunerated, publication of British writers' (2002, p. 40). Following this author,

'positions on copyright were clearly not the product of disinterested jurisprudential reflection. By the nineteenth century it became clear that nations that were net exporters of intellectual property, such as France, England, and Germany, increasingly favored the natural rights doctrine as a universal moral and economic right enabling authors to exercise control over their creations and inventions and to receive remuneration. Conversely, developing nations that were net importers of literary and scientific creations, such as the United States and Russia, refused to sign on to international agreements and insisted on the utilitarian view of copyright claims as the statutory creations of particular national legal regimes. By refusing to sign international copyright treaties, the developing nations of the nineteenth century were able to simply appropriate the ideas, literary creations, and scientific inventions of the major economic powers freely'. (p. 40).

But when the United States 'evolved from being a net importer of intellectual property to a net exporter, its legal doctrines for regulating intellectual property have tended to shift from the objectivist-utilitarian side of the legal balance toward the universalist-natural-rights side' (2002, p. 40). Therefore, instead of protecting IPR with a local perspective, international protection became necessary for the economic interests of the net exporters.

The second stage began on the 3rd of December 1887, with the entry into force of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, signed on the 9th September 1886 initially by ten countries, although applicable through the 'colonial clause' set forth in its article 19 to the European colonies (Olwan, 2013, p. 44).

The Berne Convention was based on three basic principles, which altered totally the regulation applicable before the Convention:1

-

Reciprocity between contracting parties. As per the WIPO website: 'a) Works originating in one of the Contracting States (that is, works the author of which is a national of such a State or works first published in such a State) must be given the same protection in each of the other Contracting States as the latter grants to the works of its own nationals (principle of "national treatment")'.

-

The previous registry of the work was not a requirement for its protection: 'b) Protection must not be conditional upon compliance with any formality (principle of "automatic" protection)'.

-

Best protection status: 'c) Protection is independent of the existence of protection in the country of origin of the work (principle of "independence" of protection). If, however, a Contracting State provides for a longer term of protection than the minimum prescribed by the Convention and the work ceases to be protected in the country of origin, protection may be denied once protection in the country of origin ceases'.

From the initial 10 countries, the Berne Convention has updated the number of signatories to the current number of 179 contracting parties.2 It underwent several amendments until its final version, dated 1971.

In 1967 a Convention incorporated the WIPO, which in December 1974 became a UN specialized agency responsible 'for promoting creative intellectual activity and for facilitating the transfer of technology related to industrial property to the developing countries in order to accelerate economic, social and cultural development'3 Under this new umbrella, the Berne Convention was adapted to the new context of digital technologies through the adoption of the WIPO Copyright Treaty4 and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty5 in Geneva on December 20, 1996.

Notwithstanding, although it might seem a good instrument for the author's protection, scholars such as Peter Drahos and John Braithwaite, Susan K. Sell, Joost Smiers, Marieke van Schijndel, and William Patry, among others, (Drahos, Peter & Braithwaite, John, 2002; Patry, 2009; Sell, 2003; Smiers, 2006; Smiers, Joost & van Schijndel, Marieke, 2008) have studied the disadvantages that the Berne Convention meant for political and economic interests of big corporations and States.

The limitations of the Berne Convention, primarily the impossibility to impose a third country to uphold certain conduct, lead to the third regulation stage, represented by the TRIPS Agreement. Smiers and van Schijndel summarize the necessity of the TRIPS agreement (2008, p. 58) due to the absence in the WIPO treaties of a coercive mechanism to force different countries to adapt their national legislations to the lobbies' impositions. And if public law did not allow what big transnational corporations were interested in, there was a solution: private law. Therefore, in the Uruguay Round of GATT negotiations (1986-1994) two broad groups were formed, one that discussed goods and another that discussed services. Within these two broad groups, 14 further subgroups were formed. Number 11 was the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights including Trade in Counterfeit Goods. A strict bureaucracy was imposed, with a tight timetable, which led to an easy victory of the developed countries (Drahos & Braithwaite, 2002). The work from all groups ended with the signature in Marrakesh the 15th of April 1994, the constitutive agreement of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Beside this agreement, the signatories adopted the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) which included an enforcement mechanism to oblige the States according to the interests of the right holders through a settlement resolution system under the WTO rules.

Through the TRIPS agreement, IPR rights entered the domain of trade, and a country that would not abide by the rules of the dominant states would certainly be subject to trade sanctions. IPR was no longer a matter that concerned authors, but an asset that concerned owners. As Sell stated, 'TRIPS incorporates a notion of intellectual property rights as a system of exclusion and protection rather than one of diffusion and competition. It extends rights holders' privileges and reduces their obligations' (Sell, 2004, p. 314). According to Andres B. Scwarzenberg 'The United States retains the flexibility to determine whether to seek recourse to challenge unfair foreign trade practices through the WTO or to act unilaterally' (2020, p. 2), which allows United States to identify, investigate and sanction foreign countries four types of practices (2020, pp. 5-6):

-

A denial of U.S. rights under any U.S. trade agreement by a foreign country.

-

An 'unjustifiable' action that 'burdens or restricts' U.S. commerce.

-

An 'unreasonable' action that 'burdens or restricts' U.S. commerce.

-

A 'discriminatory' action that 'burdens or restricts' U.S. commerce.

A side effect of this regulation was the imposition of a system that, only focusing in the commercial characteristic of IP works, rendered invisible a huge IP production made by collectivities under free licences, whose intention is not to trade with their works (Benkler, 2006; de la Cueva, 2012; Kelty, 2008; Lessig, 2004; Olwan, 2013; Smart et al., 2019). The global regulation only foresaw a commercial and trade panorama, and ignored that the most important intellectual work of humankind, the Internet, was created out of that paradigm. This pro commerce legislation regulates now two confronted models:

'The first model, the only one the media cares to take into account, is to protect6 work in the way property rights have always been protected: by developing mechanisms (that take the form of alarms, offendicula, fences, walls, boundaries, and other restrictions) to exclude outside use. Preventing the unauthorized use of work means markets can be created and fares can be charged for the work's use. This is the model of entertainment, of the circus, and the main model for the merchants of culture, whose icons are the blockbuster movie, the summer hit and the best selling novel, all of which are shamelessly pedaled as culture.

The second model considers that the best way to protect an intellectual work is to develop ecosystems that will allow it to reproduce. Examples include the Instituto Cervantes, Alliançe Française, the British Council, or the Goethe Institute, where the idea is not to exclude outsiders from a work or language but to disseminate it as widely as possible. This is the model of free software, of Internet protocols, of Wikipedia, or of protecting the DNA of the Iberian Lynx. This kind of system is nothing new: it has been in existence for as long as academia. But such universal collective authorship is a serious challenge to the individualistic basis of copyright, [...] In this case, wealth is not given to a minority by commercializing different, fragmented uses of a work; instead, wealth is generated for all via secondary means, in a general context of increased wealth: a country with a literate population has a higher chance of generating income than one where illiteracy prevails.' (de la Cueva, 2014, pp. 86-87).

As will be analysed in Section 5.1.3, IP is witnessing two different types of works: one that protects static works or results, and a second that protects processes. In the first type, the protection is guaranteed through the 'all rights reserved' system, which denies the usage of a work to all except to the rightholder. In the second type, the community involved in the creation uses IP to protect the process and its dynamic result. The outcome of these dynamic processes (the RFC, Wikipedia, OpenStreetMap, Linux, Apache server, etc.) would be impossible to obtain through the bureaucratic burdens posed by the 'all rights reserved' system7.

4.3. IPR economic balance¶

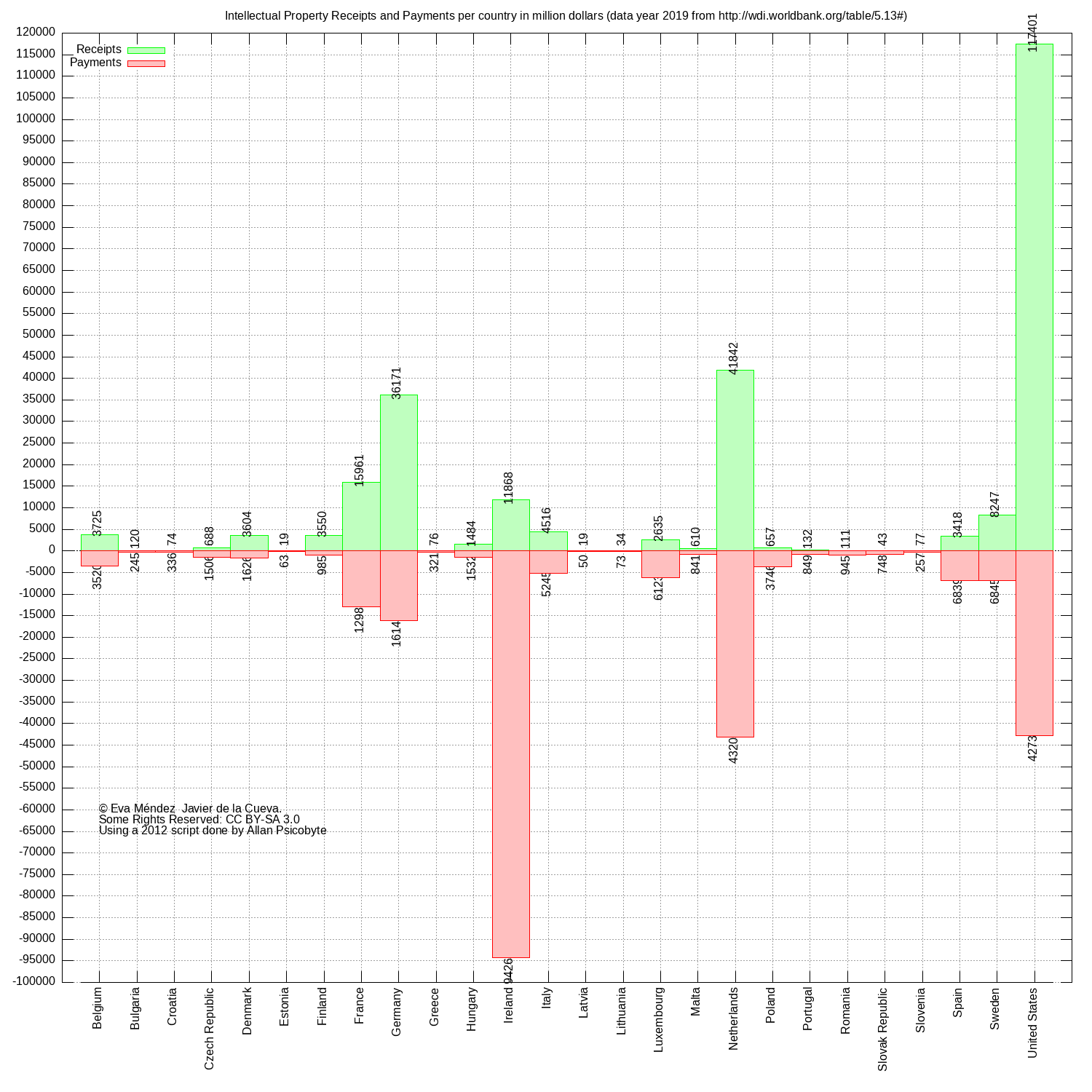

For the purposes of analysing the economic impact of IPR, open data from the World Bank8 have been downloaded, plotted and represented in the following graph (Fig. 1), where we can appreciate the balance of IPR between EU Members and the United States in million dollars. The table compares the receipts and payments for the US and the EU Members. Additionally Annex III includes a graph for all the countries of the world and a table with the data, ordered by net profit.

Fig. 1. IP receipts and payments per country.

The results of the receipts and payments per country are detailed in the following table, ordered by net profit (Table 2).

| Year 2019 | Receipts $ millions | Payments $ millions | Net $ millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 117 401 | 42 732 | 74 669 |

| Germany | 36 171 | 16 149 | 20 022 |

| France | 15 961 | 12 982 | 2 979 |

| Finland | 3 550 | 985 | 2 565 |

| Denmark | 3 604 | 1626 | 1 978 |

| Sweden | 8 247 | 6 845 | 1 402 |

| Belgium | 3 725 | 3 520 | 205 |

| Latvia | 19 | 50 | -31 |

| Lithuania | 34 | 73 | -39 |

| Estonia | 19 | 63 | -44 |

| Hungary | 1 484 | 1 532 | -48 |

| Bulgaria | 120 | 245 | -125 |

| Slovenia | 77 | 257 | -180 |

| Malta | 610 | 841 | -231 |

| Greece | 76 | 321 | -245 |

| Croatia | 74 | 336 | -262 |

| Austria | 1 421 | 2 091 | -670 |

| Slovakia | 43 | 748 | -705 |

| Portugal | 132 | 849 | -717 |

| Italy | 4 516 | 5 245 | -729 |

| Czechia | 688 | 1 506 | -818 |

| Romania | 111 | 945 | -834 |

| Netherlands | 41 842 | 43 203 | -1 361 |

| Poland | 657 | 3 746 | -3 089 |

| Spain | 3 418 | 6 839 | -3 421 |

| Luxembourg | 2635 | 6 123 | -3 488 |

| Ireland | 11 868 | 94 262 | -82 394 |

Table 2. IPR receipts and payments of US and EU (European Member States).

The World Bank data evidences that the net profit of the United States is 74 669 million USD, more than three times the net profit of Germany, the second country in the list. Ireland's negative balance of -82 394 million USD is not due to extreme IP consumption, but because of its role as a tax haven used by imaginative accountants.

The accrued figure of EU members in comparison with the United States is included in the Table 3 below.

| Year 2019 | Receipts $ millions | Payments $ millions | Net $ millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 117 401 | 42 732 | 74 669 |

| EU | 141 102 | 211 382 | -70 280 |

Table 3. IPR receipts and payments in US and EU (aggregated figures).

What we find relevant from the above table is that IPR have a geopolitical importance and that the European Union does not occupy a relevant place, notwithstanding the self-interests of its members Germany, France, Finland, Denmark, Sweden and Belgium, the only six States who have a positive balance.

4.4. The myth of innovation and the lack of data¶

First came innovation and intellectual works, then came IPR. It is not a chicken and egg problem, as it is evident that humankind has been creative since its appearance as a species. For thousands of years, there has been creativity and innovation without legal regulation. Therefore, it cannot be stated that without IPR, innovation and creativity would not exist. On the contrary, they already existed before the laws that 'protect' them were drafted. All innovation and all intellectual works created before IPR were born demonstrate this assertion. It is indisputable that the nuclear part of the occidental cultural canon was born before IPR were even envisaged. IPR are created as a social construct to regulate a domain that already existed without rules. The assumption that creativity and innovation only exist if IP regulation exists is false, it is challenged by ethnographic, anthropological, cultural and art studies (Groĭs, 2008, pp. 93-100, 2016; Sontag, 1994, pp. 263-274; Steyerl & Berardi, 2012, pp. 31-45; Williams, 2011, pp. 48-71, 2017, pp. 19-60). If there is something that anthropology has demonstrated, it is that culture is able to exist with no IPR at all.

As Jessica Silbey studied in her book The Eureka Myth: Creators, Innovators, and Everyday Intellectual Property, 'Taking the data from these fifty interviews as a starting point, we begin to understand that the long-standing and resilient incentive story of IP---that strong property rights are necessary to promote science and the arts---is false' (Silbey, 2015, p. 15). This assertion, that IP is necessary for creativity, is also challenged by other authors (Boldrin & Levine, 2008; Darling & Perzanowski, 2017; Lessig, 2004; Raustiala & Sprigman, 2019; Smiers, 2006; Sprigman, 2017). Furthermore, there are spaces where IPR are considered a barrier to creativity (Bach et al., 2010; Elkin-Koren & Salzberger, 2013, p. 112; Lessig, 2004, 2008; Vaidhyanathan, 2001). Kate Darling and Aaron Perzanowski have convincingly studied spaces where there is creativity without law, such as cuisine, cocktails, medical procedures, tattoo industry, graffiti,9 architecture, unique roller skaters' pseudonyms, pornography and Nigerian Cinema (Darling & Perzanowski, 2017). Sprigman adds fashion design, financial instruments, sports play, stand-up comedy, fan fiction and professional magic (2017, p. 466). In addition to the examples provided by these authors, legal domain production could be included: judicial decisions do not need IPR in order to be of more or less creative or to be of more or less quality and 'practices of Canadian legal professionals suggest that lawyers rarely appeal to formal IP law to regulate information exchanges among them, relying instead on informal norms and practices' (Piper, 2014, p. 111). Analysing this relationship, Kal Raustiala and Christopher Jon Sprigman have coined the concept of the 'negative space of IP'. They explain it as follows:

'Innovation is a substantial part of any flourishing contemporary economy; it is arguably the key source of growth in advanced economies today. And it is widely believed that innovation rests upon---and indeed requires---strong IP protection. Given this, it is surprising how little empirical evidence supports this theory. Indeed, some prominent IP scholars have gone so far as to call IP's rationale fundamentally 'faith-based'. The most important task that law and economics research can undertake in the IP field is to shed light on how well IP law's core incentives model holds up in the real world. The study of IP's negative space is part of this endeavor. If healthy innovation is observed in IP's negative space, understanding why is essential.

IP's negative space is perhaps most simply identified by contrasting it with IP's positive space. The positive space encompasses all those creative activities that IP law addresses, such as novels, poems, films, television shows, music, software, painting, and video games. The negative space of IP, by contrast, encompasses any other creative art, craft, or act that does not enjoy or at least does not ordinarily rely on IP rights against copyists, either because IP is formally inapplicable or because something---perhaps a social norm against IP enforcement, or a legal or economic barrier that discourages resort to formal IP---limits its salience.' (Raustiala & Sprigman, 2019, p. 311).

A different question that must be considered would be whether current regulation fosters or hampers innovation, but it seems on this point the existent data are not conclusive. The gross figures about the importance of IPR in the GDP of countries lacks minimum qualitative analysis, they are built on presumptions they never demonstrate, and cannot evaluate neither the innovation aspect nor others. Even the creators' behaviour does not follow rational rules as Bechtold, Bucaffusco and Sprigman concluded after running 4 experiments: 'Often, but not always, these heuristics lead creators to make poor choices. Many creators choose to innovate even though they would be much better off borrowing, and many other creators choose to borrow when doing so is clearly suboptimal.' (2016, p. 1253). As Mark A. Lemley puts it in his article Faith-Based Intellectual Property:

'The problem isn't that we don't have enough evidence, or the right kind of evidence. The problem is that the picture painted by the evidence is a complicated one. The relationship between patents and innovation seems to depend greatly on industry; some evidence suggests that the patent system is worth the cost in biomedical industries but not elsewhere. Copyright industries seem to vary widely in how well they are responding to the challenge of the Internet, and their profitability doesn't seem obviously related to the ease or frequency of piracy. The studies of the behavior of artists and inventors are similarly complicated. Money doesn't seem to be the prime motivator for most creators, and sometimes it can even suppress creativity. And an amazing number of people seem perfectly happy to create and share their work for free now that the Internet has given them the means to do so. At the same time, the money provided by IP allows the existence of a professional creative class that may be desirable for distributional reasons or because we like the sorts of things they create more than we do the work of amateurs. The decidedly ambiguous nature of this evidence should trouble us as IP lawyers, scholars, and policymakers.' (Lemley, 2015, p. 1334).

Lemley's article provides an extensive list of references to empirical work on 'virtually every aspect of IP law and innovative and creative markets' made in the last 30 years: who obtains IP rights, who enforces them, who wins, how IP rights affect stock performance, what drives creativity in virtually every field, including those protected by patents, by copyright, and by no IP right at all, how innovation has succeeded under IP changes, the growth of the Internet, how subjects envision the sale of things they have created, games that model economies with different IP regimes, surveys of creators and inventors about their motivations and psychological studies that study why and how people create and the relevance of money in their creative impulse (Lemley, 2015, p. 1333).

In the same sense, authors such as William M. Landes and Richard A. Posner have stated that 'Economic analysis has come up short of providing either theoretical or empirical grounds for assessing the overall effect of intellectual property law on economic welfare' (Landes & Posner, 2003, p. 422); the GAO stated that 'Most experts we spoke with and the literature we reviewed observed that despite significant efforts, it is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify the net effect of counterfeiting and piracy on the economy as a whole' (United States Government Accountability Office, 2010, pp. 15-16); For Albert G.Z. Hu and Adam B. Jaffe, 'Even within the technologically advanced world, there is surprisingly little empirical evidence for the proposition that stronger IPR regimes produce faster innovation' (Hu & Jaffe, 2014, p. 106); Brian T. Yeh, in a report for the United States Congress, enumerates the difficulties posed to calculate trade secret infringements due to the variables that operate, one of which is the impossibility 'to measure the monetary value of some forms of sensitive information' (Yeh, 2016, pp. 13-14); Xabier Seuba asserts that 'estimates concerning the scale of infringement, the value of intellectual property or the impact of intellectual property infringement have been elaborated by private stakeholders who often have a direct interest in the object of analysis' (Seuba, 2017, p. 67) and finally Robert P. Merges, in an opinion which may be reasonable in certain domains but should not be acceptable for OS policymakers, has made it clear in his book Justifying Intellectual Property that what drives him is 'faith':

'This is a truth I avoided over the years, sometimes more subtly (for example, heavily weighing the inconclusive positive data, showing IP law is necessary and efficient, discounting inconclusive data on the other side), and sometimes less so (ignoring the data altogether, or pretending that more solid data were just around the corner). But try as I might, there was a truth I could never quite get around: the data are maddeningly inconclusive. In my opinion, they support a fairly solid case in favor of IP protection---but not a lock- solid, airtight case, a case we can confidently take to an unbiased jury of hardheaded social scientists.

And yet, through all the doubts over empirical proof, my faith10 in the necessity and importance of IP law has only grown.' (Merges, 2011, p. 3).

In order to build a scientific discipline, the problem that arises under these data conditions have been studied by Böschen et al under what is known as 'nonknowledge'. First, there is a political issue between the groups involved: 'control-oriented epistemic cultures are faced with the threat of losing their authority to define the unknown and its relevance' (Böschen et al., 2010, p. 802). It is evident that in the IP domain a myriad of data is produced by parties who benefit from biased data. Second, to maintain the statu quo, the no-knowledge is substituted with no-auditable data. It would be very interesting to know how many sectors live due to 'antipiracy' and what their incomes are. The practice of providing biased data is very common and is one of the fundamentals of 'agnotology', the cultural production of ignorance, as studied by Robert N. Proctor and Londa Schiebinger (2008). Science mandates scepticism, that is to say, a special care has to be taken when blindly accepting data collected by a lobbying party and developing public policies based on an 'no-known'.

4.5. IPR in the European Union¶

The EU approach to IPR legislation is based on the principle of territoriality. According to Kur and Dreier, this approach implies 'that national rules govern copyrighted subject matter within the territory of a given Member State. It also means that -- absent a community-wide copyright -- one and the same work is protected by different laws in each of the EU Member States' (Kur & Dreier, 2013, p. 243). The regulation of IPR subject matter is based on different Directives, which design general frameworks later transposed by the national Members. It is well known that the regulation through Directives has the consequence of not producing a full harmonisation, despite the existence of autonomous concepts of EU law that may be interpreted by the European Court of Justice.

4.5.1. Copyright¶

As described above, Copyright is regulated by a hierarchical system composed by the WIPO treaties and the TRIPS Agreement. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (as amended on September 28, 1979)11 regulates from article 2 to 20, among other aspects, the protected works, the possible limitations, the criteria of eligibility for protection, the rights guaranteed, the possible restriction of protection, the moral rights, the term of protection, the right of translation, the right of reproduction, certain free uses of works, rights in dramatic and musical works, broadcasting, rights in literary works, right of adaptation, arrangement or other alteration, cinematographic and related rights, droit de suite, right to enforce the protected rights, seizure of infringing copies, control of circulation of works and expiry of protection. The Berne Convention has been updated and complemented with the WIPO Copyright Treaty12 and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty13, to adapt WIPO treaties to the Internet.

The TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) agreement refers in articles 9 through 15 to articles 1 through 21 of the Berne Convention in its 1971 version. In this way, the TRIPS Agreement extends the Berne Convention and includes new regulations regarding computer programs and compilations of data (article 10), rental rights of 'at least computer programs and cinematographic works' (article 11), term of protection no less than 50 years for all works except photographic works (article 12), limitations and exceptions to exclusive rights 'which do not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the right holder' (article 13) and protection of performers, producers of phonograms and broadcasting organisations (article 14).

Regarding the EU,14 the regulation of copyright is contained in different Directives and Regulations that follow the WIPO treaties and the TRIPS agreement. European norms encompass diverse thematic areas, as shown in Table 4 below:

| Directive/Regulation | Regulated content |

|---|---|

| Directive 93/83/EEC.15 Amended by Directive (EU) 2019/789216 | Satellite broadcasting and cable retransmission |

| Directive 96/9/EC17 Amended by Directive (EU) 2019/790218 | Databases |

| Directive 2001/29/EC19 Amended by Directive (EU) 2017/156420 and by Directive (EU) 2019/79021 | Harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society |

| Directive 2001/84/EC22 | Resale right of an original work of art |

| Directive 2004/48/EC23 (Corrigendum24) | Enforcement of intellectual property rights |

| Directive 2006/115/EC25 | Rental right and lending right and on certain rights |

| Directive 2006/116/EC26 Amended by Directive 2011/77/EU27 | Term of protection |

| Directive 2009/24/EC28 | Computer programs |

| Directive 2011/77/EU29 | Term of protection |

| Directive 2012/28/EU30 | Orphan works |

| Directive 2014/26/EU31 | Collective management of copyright and related rights and multi-territorial licensing of rights in musical works for online use in the internal market |

| Regulation (EU) 2017/112832 | Cross-border portability of online content services in the internal market |

| Directive (EU) 2017/156433 | Certain permitted uses of certain works and other subject matter protected by copyright and related rights for the benefit of persons who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print-disabled |

| Regulation (EU) 2017/156334 | Cross-border exchange between the Union and third countries of accessible format copies of certain works and other subject matter for the benefit of persons who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print-disabled. |

| Directive (EU) 2019/78935 | Satellite broadcasting and cable retransmission |

| Directive (EU) 2019/79036 | Copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market |

Table 4. Summary of EU Regulation regarding IPR issues (Regulation-Issues covered).

Authors and works

Copyrights over intellectual works are created from the fixation of the work in some material form (art. 2.2 Berne Convention). No further formal requirement is needed.

An author of an intellectual work must be a natural person, although in certain cases a moral person can be considered. There are discussions on who is to be considered an author when it relates to the participation of natural persons in collective filmography works (Bowrey & Handler, 2014) due to the dual participation of director and producer, or when a work is the result of the usage of technology (Eno, 1979). Regarding authorship, one of the novelties that Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) have allowed is collective creation (Benkler, 2006). Websites such as Wikipedia, Github or OpenstreetMap are designed for this purpose and facilitate a common usage by contributors and the public, allowing a transparent review of the different contributions from the authors, who chain their work to a previous version. This peculiarity facilitates a double role of a user and author of an intellectual property work simultaneously. Using the Wikipedia example, when a person connects to the web site and reads a page, her role is as a user. But suddenly this person decides that there is some information she wants to include, clicks on the edit form, alters the previous work, and submits the form. This possibility to transform oneself nearly instantly from user to co-author, with no further planification, is only possible when the technology has developed platforms that allow it. As we will explain below, this way of working is only possible through an IPR permissive licencing model.

It should not be necessary to mention that the author has to be a person, but there are discussions in two areas. First, the famous case of Naruto, a monkey that took several photographs of himself with a journalist's camera (the monkey selfie case), was subject to controversy in the United States. The first instance ruling stated that there is no mention of animals anywhere in the Copyright Act, which was confirmed by the Court of Appeal.37 The concept of authorship is not extended to animals.

Second, there is no clear answer as yet to the question of the authorship of computer generated works. Perry and Margoni propose four possible answers: a) the author of the program; b) the user of the program; c) the program; and d) none (public domain) (2010). On the contrary, Grimmelmann argues that computer-authored works do not exist (Grimmelmann, 2016, p. 403) and therefore it is a question that needs no answer. According to this author, nearly all works created nowadays are made using computers, and where algorithms are used, there is no reason why these creations should have a different status, as 'All creativity is also algorithmic in the sense that we could encode the work as a program making completely explicit what the creator did to produce it.' (2016, p. 409). Other ways to create works such as sequential or nondeterministic uses of computer programs can neither be acceptable to create copyright. Grimmelmann uses the Spirograph as an example of sequential work to assert that the result is the same no matter who the user is. And related to nondeterministic creations, where the author uses some variable elements to produce a work, it cannot be accepted simply because 'Dice are not authors, and neither are computer programs' (p. 414). Andrés Guadamuz remembers that 'Most jurisdictions, including Spain and Germany, state that only works created by a human can be protected' (2017, p. 17). As referred by Guadamuz, EU38, US39 and Australian40 courts have denied the possibility of a computer being an author, but there are jurisdictions (Hong Kong -SAR-, India, Ireland, New Zealand and the UK) where there is a specific provision that considers author the person 'by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken'41.

Regarding the subject matter of protection, the Berne Convention states what we should consider as a work subject to copyright regulation. This field of IPR regulates productions in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, independently from their form of expression. The only requirement is that the work must be original. This condition is only applicable to the work, not to the ideas that underpin it, as it is clearly stipulated in article 9.2 of the TRIPS agreement: 'Copyright protection shall extend to expressions and not to ideas, procedures, methods of operation or mathematical concepts as such.' The multiplicity of works that are subject matter of copyright responds to creativity. Some of the most compelling ones are John Cage's musical piece entitled 4,33, which refers to 4 minutes and 33 seconds where the performer is in complete silence, Dieter Roth's organic decomposition sculptures, or the works by Alexander Orion, who uses the technique known as reverse graffiti, where instead of painting a public space cleans a dirty surface. Art has little limits when challenging itself with traditional concepts of intellectual property and all of them fall under copyright regulation.

Rights and their limitations

As stated before, from the creation of the work, with no other formality, the author is entitled to two different sets of rights: moral and economic.

The moral rights are the direct heirs of the French origin of IPR, as they hold a direct connection with the personality of the author. They are regulated in Article 6 bis of Berne Convention as follows:

'(1) Independently of the author's economic rights, and even after the transfer of the said rights, the author shall have the right to claim authorship of the work and to object to any distortion, mutilation or other modification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, the said work, which would be prejudicial to his honor or reputation.

(2) The rights granted to the author in accordance with the preceding paragraph shall, after his death, be maintained, at least until the expiry of the economic rights, and shall be exercisable by the persons or institutions authorized by the legislation of the country where protection is claimed. However, those countries whose legislation, at the moment of their ratification of or accession to this Act, does not provide for the protection after the death of the author of all the rights set out in the preceding paragraph may provide that some of these rights may, after his death, cease to be maintained.

(3) The means of redress for safeguarding the rights granted by this Article shall be governed by the legislation of the country where protection is claimed.'

Economic rights are related to the use of the work. It is the author's exclusive decision to allow activities involving the creation. These activities depend on the jurisdiction but are generally limited to four: to reproduce (or copy) the work, to alter it (or to make derivative copies), to distribute or to publicly communicate it. The author may trade these activities, conferring the right to exercise one or more activities to a third party. This assignment may be done by written agreement, clicking on a web page, by a public licence or by any other legal instrument. The rights over these activities are known as the 'exclusive rights', but they are not the only economic rights. In addition to the exclusive rights, the rightholder of the work may receive so-called remuneration rights. The reason to be entitled to this second category of economic rights originates in the existence of certain activities exercised over intellectual works that are impossible to control (for example, scanning a book at home or recording a film from TV) or that seem reasonable, as they could be considered as an ius usus inocui over the work, even if they consist in one of the four exclusive activities (copy, alter, distribute or communicate to the public). These activities are known as the 'Exceptions or limitations' of copyright and may be configured legally either as a closed list, which is the European system (article 5 if the Directive 2001/29/EC) or as requirements open to judicial interpretation, which is the 'doctrine of fair use',42 system used in the United States. The remuneration rights are directly connected to these exceptions or limitations. As stated in the law, some of them are cost free but others imply a payment. This payment is the so-called remuneration right.

Termination of copyright

The termination of copyright is no less than 50 years after the death of the author, according to article 7 of the Berne Convention, which allows its signatories to extend it. The same term is included in article 12 of the TRIPS Agreement. EU regulates termination in its Directive 2006/116/EC43, amended by Directive 2011/77/EU44, where the term of protection for literary, artistic and scientific works is 70 years, 'calculated from the first day of January of the year following the event which gives rise to them'45. To summarize what has been explained before, two perspectives may be useful, as shown in Table 5 below.

+------------------------------------+---------------------------------+

| **Author's perspective** | **User's perspective** |

+====================================+=================================+

| The creation produces instantly | The rule by default is that the |

| two sets of rights: | user may not exercise any |

| | activity over the work, unless: |

| 1. Moral rights (they refer to | |

| the personality of the | 1. The owner accepts for a |

| author). | price or *gratuit* that the |

| | user exercises over the |

| 2. Economic rights. They refer to | work one or more activities |

| economic transactions. There | that are included in the |

| are two types of economic | exclusive rights. |

| rights: | |

| | 2. The user exercises a |

| - Exclusive rights: received by | limitation. The exercise of |

| trading with the consent of | a limitation may trigger a |

| activities done with the work. | remuneration in favour of |

| | the rightholder. |

| - Remuneration rights: a payment | |

| to compensate for the use of a | 3. The work is under public |

| limitation. | domain. In this case, no |

| | consent is necessary. |

+------------------------------------+---------------------------------+

Table 5. Author and user perspective of rights and activities over a work.

In this normative context is where science has to communicate to the public its results. One of the reasons why science needs to be public is because it must be 'falsifiable' and to become public at least two activities (reproduction and distribution or reproduction and public communication) are needed. IPR and its default 'all rights reserved' rule operate in one of the core necessities of science: public dissemination to allow public scrutiny.

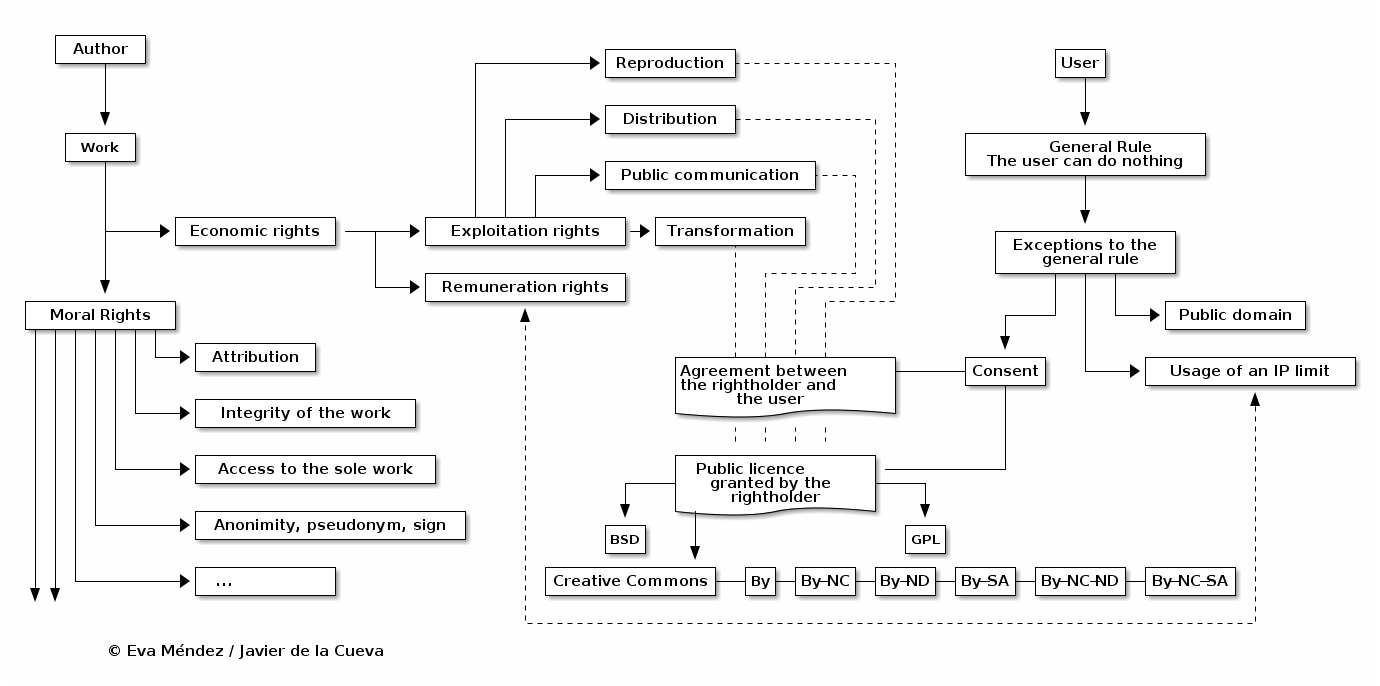

Fig. 2. Copyright author, work, rights, activities, limits and consent scheme.

How have open knowledge activists dealt with openness?

As previously stated and shown in Fig. 2 above, there are only two possible legal pathways to reproduce, alter, communicate to the public or distribute a work subject to current copyright: either obtain the consent of the right holder, or exercise a limitation. 'Scientific communities are communication systems' (Stichweh, 2001, p. 288), therefore open knowledge activists have worked trying to enhance both possibilities: on one hand, making authors declare that certain uses of the works are permissible, which has been done by disaggregating the copyrights over a work and announcing publicly the allowed activities through the attachment of a free licence. On the other, trying with little success to expand the copyright exceptions based on research or on scientific uses46.

One of the main contributions to this field has been made by the Nobel laureate Elinor Ostrom and her colleague Charlotte Hess. During her career, Ostrom studied common goods, understood as shared natural resources, which lead to finding an analogous nature between the traditional commons and the 'academic research, open science, traditional knowledge, and the intellectual public domain' (Hess & Ostrom, 2003). Hess and Ostrom produced their seminal article Artifacts, Facilities, and Content: Information as a Common-pool Resource (Hess & Ostrom, 2003) with the goal of summarizing 'the lessons learned from a large body of international, interdisciplinary research on common-pool resources in the past twenty-five years and consider its usefulness in the analysis of scholarly information as a resource'.

One of the key points studied in their article was to assess which of the aspects related to intellectual property rights were relevant for researchers:

'Property rights define actions that individuals can take in relation to other individuals regarding some- "thing." If one individual has a right, someone else has a commensurate duty to observe that right. Schlager and Ostrom identify five major types of property rights that are most relevant for the use of common-pool resources, including access, extraction, management, exclusion, and alienation. These are defined as:

Access: The right to enter a defined physical area and enjoy non subtractive benefits (e.g., hike, canoe, sit in the sun).

Extraction: The right to obtain resource units or products of a resource system (e.g., catch fish, divert water).

Management: The right to regulate internal use patterns and transform the resource by making improvements.

Exclusion: The right to determine who will have access rights and withdrawal rights, and how those rights may be transferred.

Alienation: The right to sell or lease management and exclusion rights.' (Hess & Ostrom, 2003).

Therefore, the relevant aspects of property in the digital domain were, according to these authors, different from the traditional ones. The reason, although it is not made evident by them, is that information in the digital age is just a list of ones and zeros. Hence to be the 'owner' of information in reality is to be entitled to some rights over such a list. As Marcelo Corrales puts it, 'Insofar as it refers to data, the concept of "ownership" is not a legal construct. This notion has been borrowed from tangible properties and is used as an analogy, which is extended to intangible rights such as data or information' (Corrales Compagnucci, 2020, p. 7). Based on these findings, three years later, in the spring of 2004, Hess and Ostrom conducted a Workshop on Scholarly Communication as a Commons, which fructified in a book edited by both scholars, Understanding Knowledge as a Commons (Hess & Ostrom, 2007). The workshop participants sought to:

'[...] integrate perspectives that are frequently segregated within the scholarly-communication arena, such as intellectual property rights; information technology (including hardware, software, code and open source, and infrastructure); traditional libraries; digital libraries; invention and creativity; collaborative science; citizenship and democratic processes; collective action; information economics; and the management, dissemination, and preservation of the scholarly record.' (Hess & Ostrom, 2007, p. xi).

The contributors to Hess and Ostrom's edited book were David Bolier, Nancy Kanich, James Boyle, Donald J. Waters, Peter Suber, Shubha Ghosh, Peter Levine, Charles M. Schweik, Wendy Pradt Lougee, James C. Cox and J. Todd Swarthout; relevant and distinguished scholars in the field of knowledge studies. Based on the theories that Robert K. Merton wrote in his 1942 essay, The Normative Structure of Science (Merton, 1974), James Boyle asserted in the chapter he wrote for this book that 'Access to and citation of the peer-reviewed literature is crucial to the scientific project as Merton describes it, indeed it is one of its principal methods of error correction'. (Boyle, 2007, p. 123). But instead of favouring this necessary activity for science, Boyle claims that copyright now is acting as a 'fence', preventing access to works. Boyle distinguishes the existence of two types of information in the Internet: data, which are not subject to copyright, and works under this regulation. The comparison between how data are creating knowledge but works under copyright are not, as they are unusable due to IP regulation, makes him pose the following question:

'Working in an arena where facts are largely free from intellectual property rights, the Net has assembled a wonderful cybernetically organized reference work. What might it do to the 97% of the culture of the twentieth century that is not being commercially exploited if that culture was available for everyone to annotate, remix, compare, compile, revise, create new editions, link together in archives, or make multimedia reference works?' (Boyle, 2007, p. 139).

As Boyle finally states:

'[S]uccessful commons are frequently characterized by a variety of restraints---even if these are informal or collective, rather than coming from the regime of private ownership. It even gives us generalizable tools that can help us to match types of resources with types of commons regimes. The web confirms those lessons. As I pointed out earlier, standard intellectual property theory would posit that to get high-quality factual reference works, we need strong property rights and single-entity control for at least three independent reasons related to the tragedy of the commons: the need for exclusive control over reproduction in order to produce the incentives necessary for large-scale investment in writers and fact-checkers, the need for control over content and editing in order to ensure quality, and the need for control over the name or symbol of the resource itself as a signal to readers and an inducement to invest in quality in the first place.'

Therefore, the mertonian Universalism, Communism, Disinterestedness and Organized Skepticism, the four sets of institutional imperatives, cannot be achieved with digital technologies if IP, instead of being a system of rewards, consists in a system of payments not to the contributors to science but to intermediaries only interested in monetary incomes.

The possibility to disintegrate intellectual property from its traditional understanding into different components is also referred to by the Brazilian philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger. In his book The Knowledge Economy (Unger, 2019), he dissects the different rights that can be included in the digital IPR. The conclusion that may arrive from the Hess, Ostrom and Unger thesis is that the concept of IP ownership is not relevant in the digital age: what are crucial are the different possibilities attached to the possession or access of a digital information:

'An advantage of the unified property right is that it allows a risk-taking entrepreneur to do something in which no one else believes without having to avoid potential vetoes by multiple stakeholders. Its disadvantage is the reverse side of this benefit. It fails to provide a legal setting for the superimposition of stakes of different kinds, held by multiple stakeholders, in the same productive resources. For that use, we need fragmentary, conditional, or temporary property rights, resulting from the disaggregation of unified property.' (Unger, 2019, pp. 125-126).

According to Unger, IPR are not only a matter of sharing knowledge but exercising power. As it is largely known, the companies that own scientific publications exercise a control contrary to the interests of universities and other research centres (Larivière et al., 2015).47 Therefore, in order for the knowledge economy to flourish, this control must stop:

'An area of reform in the property regime that is vital to the future of the knowledge economy is intellectual property. The established law of patent and copyright, largely a creation of the nineteenth century, inhibits the development of an inclusive vanguardism. It does so chiefly by imposing a highly restrictive grid on the ways in which economic agents can participate in the development of the knowledge economy and share in its rewards. Its practical effect is to help a small number of mega-enterprises dominate the vanguards of production by holding exclusive rights to key technologies that they have either developed themselves or bought from the original inventors. The excuse for concentrating such rents in a small set of capital-rich economic agents is the need to provide incentives to innovation, compensating those who have made long bets on an improbable future. The consequence, however, is to benefit a few only by discouraging and excluding many. It also further enhances the already overwhelming advantages of large scale in the control of the knowledge economy.' (Unger, 2019, pp. 127-128).

Nevertheless, as it is evident, although we focus on possession of the information and not on its property, under current regulations consent is still needed in order to exercise rights over the content, and the problem is that the authors are no longer the rightholders so their consent means nothing. Trying to resolve this issue, the Open Access movement crystallized its first declaration in Budapest (BOAI48), on the 14th February, 2002. Its first paragraph is notable:

'An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarly journals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge. The new technology is the internet. The public good they make possible is the world-wide electronic distribution of the peer-reviewed journal literature and completely free and unrestricted access to it by all scientists, scholars, teachers, students, and other curious minds. Removing access barriers to this literature will accelerate research, enrich education, share the learning of the rich with the poor and the poor with the rich, make this literature as useful as it can be, and lay the foundation for uniting humanity in a common intellectual conversation and quest for knowledge.'

The call made by the signatories of the BOAI was to remove the financial, legal, or technical barriers that stood in the way of gaining access to content. The two solutions proposed by the Open Access movement were self-archive and open access journals.

One of the signatories of the BOAI was Peter Suber. His work as Director of the Harvard University Office for Scholarly Communication is a leading voice in the access to free knowledge and his book Open Access (Suber, 2012) has been an important step to explain the different affordances of scholar literature, demonstrating how the granularity of the IPR rights must be taken into consideration. As Suber puts it,

'Authors who retain rights don't violate rights belonging to publishers; they merely prevent publishers from acquiring those rights in the first place. When rights-retaining authors make their work OA, publishers can't complain that OA infringes a right they possess, only that it would infringe a right they wished they possessed.' (Suber, 2012, p. 128).

Using a centralized organization as IPR trustee

In the search of shared knowledge, disaggregating rights has not been the only strategy. A very successful approach has consisted in asking all the contributors of a collective work for the non-exclusive assignment of the right to publish, distribute, make derivative works, translate, display their collaborations on the work and the right to sublicense these rights in favour of all other contributors of such work. A central organization operates as a trustee, holding the rights conferred by the collaborators, who as said do not grant the trustee exclusivity for their contributions, and grants sublicenses to all other participants of the building process of the common work. The trustee's name is the 'IETF Trust' (Internet Engineering Task Force), the intellectual property work consists, at the time of this writing, of 9.035 documents entitled RFC (Request For Comments)49 and the IP protected result is known as 'The Internet'.

An emphasis must be added on the IP nature of 'The Internet'. Every document of the set of the 9035 RFCs is a text protected by IP itself. The totality of them has the same legal consideration as any encyclopedia and is protected under the same laws.

The title RFC connects this recent technology with the traditional values of science: requesting comments in public follows the same principle that guided Oldenburg in 1665 to shift from a secret log book to an open Philosophical Transactions journal (Johns, 2009, p. 61). To ask for contributions is a way to exercise the enlightened tradition of obtaining value through the interchange of ideas, reflected in the mertonian Communism in the sense that 'The substantive findings of science are a product of social collaboration and are assigned to the community' (Merton, 1974, p. 273). But instead of grounding the mertonian Communism in social norms, IETF uses the law, IP law, establishing compulsory rules for all participants, which are to assign their IPR to the IETF Trust, while at the same time they receive a licence from this organisation to use all the material already written by prior contributors. These legal conditions are the subject matter of the RFC number 5.37850, entitled Rights Contributors Provide to the IETF Trust, where the applicable IP conditions, specially copyright and patents, can be consulted.

It is also worth quoting IETF page on IPR, which is a good summary of how the most relevant IP work of all times has been built :

'Defining characteristics of IETF standards include that they are freely available to view and read, and generally free to implement by anyone without permission or payment.

Developed through open processes51, once a standard is published as an RFC52, anyone can download and read it from the RFC Editor53 or IETF Datatracker54 websites. Further reproduction of whole RFCs (including translation into a language other than English) has been allowed and is encouraged. To indicate this, most RFCs include the standard phrase, "Distribution of this memo is unlimited". The IETF's rules on copyright issues, including use of extracts, are described in more detail in BCP 7855.

During the standards process any IETF contribution covered by patents or patent applications owned by a participant or their sponsor must be disclosed, or they must refrain from participating. A contribution is any submission to the IETF that is intended for publication as all or part of an Internet-Draft56 or an RFC, or any statement made within the context of an IETF activity such as a working group discussion on a mailing list or during a meeting. BCP 7957 provides a more complete description of how Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) are handled in IETF standards processes. The IETF Datatracker maintains a list of IPR disclosures made to the IETF.58

Beyond IETF RFCs, the IETF operates in an open and transparent fashion, publishing records59 of most of the contributions, submissions, statements and communications freely available. This includes mailing list archives,60 working group activity,61 and meeting proceedings62.'

IETF information about its IPR conditions makes evident that its inspiration comes from the scientific domain. Science is not only made through formal contributions, but also through conversations held in mailing lists, activities in working groups and in meetings (Bradner, 1999, pp. 51-52). In addition, the Internet has a common characteristic with basic science: they both serve for innovation, but it is impossible to foresee when or how the innovative results will appear, or what wealth they will produce. For example, Google, the wealthiest company in the world, is based on two free mechanisms: the first is the traditional bibliographic reference system that Google uses to calculate a web page rank; the second is the RFCs protocols. The success of this company is an interesting demonstration of the emergent possibilities of free knowledge. Furthermore, RFCs technologies are omnipresent, free of use for everybody, and serve as the common base where the 'sweat of the brow' allows appropriation of the results. RFCs have created a new scenario, the digital, that is accrued to the traditional ones and that allows for constant wealth production and its appropriation by the individuals, companies or organizations who create it.

It is also worth mentioning the epistemic blindness found in literature reviews about the wealth produced by RFCs. For example, there is no mention of these protocols nor to their contributions in the report Enquiries Into Intellectual Property's Economic Impact (OECD, 2015a), the recent A roadmap toward a common framework for measuring the Digital Economy (OECD, 2020), or in the WIPO Intellectual Property Handbook (WIPO, 2008), as if the only possible IPR were the 'all rights reserved' option. This last publication has two chapters, one related to The Promotion of Innovation (WIPO, 2008, pp. 168-171) and other referred to The Teaching of Intellectual Property Law (WIPO, 2008, pp. 421-432) where the only existent IPR are the restrictive ones where all uses are forbidden except if they are commercialized. In the literature subject matter of this review, there are very few exceptions to this epistemic blindness, and the ones that exist are very illustrative (Benkler, 2006; Helfrich & Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, 2012; Kelty, 2008; Lessig, 2004; Olwan, 2013). The Internet is considered by mainstream IP specialists and doctrine to be a new technology that challenged the old IPR statu quo and fostered piracy, but it has not been even considered as an IP work per se. A new technical encyclopedia, the RFCs, has revolutionized the world and yet is taken for granted and rendered invisible, even though it is the knowledge without which the infrastructure of our present world would not function.

Recommendation for policy makers

-

Facilitate the creation of an international organisation/body to be the trustee of all IPR related to science. This organisation will have the functions of defending openness in science. Therefore, its role cannot be held by organisations that traditionally have demonstrated epistemic blindness to shared IPR.

-

Creation of an Office for Free Intellectual Property Rights and Open Science (OFIPROS) inspired in the office subject matter of the Regulation (EU) No 386/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 20121 and in line with the new IP Action Plan as stated in the New ERA and the New Industrial Strategy for Europe communications. If under a hostile context, free intellectual property models have built the Internet, the capacity of this model to work in a favourable context within the new strategy for knowledge valorisation should be explored.

4.5.2. Patents¶

Brief historical introduction

The history of patents runs separately from copyright due to taxonomic distinctions made from the eighteenth century onwards, although both concepts have a common origin: privileges that took various forms, from exclusive monopolies for inventors to exploit their work, to printing privileges for publishers or authors (Kostylo, 2010, pp. 21-22). Following Joanna Kostylo, in these initial times the focus was more on the printing press than the immaterial corpus mysticum of an intellectual work, which could have explained their common origin. According to this author, 'Ever since the thirteenth century, the Venetians led Europe in their efforts to attract foreign expertise by granting monopoly rights to immigrants who brought with them new skills and techniques to the city'; the 'most famous patent was a five-year monopoly granted on 18 September 1469 to a German print master Johannes of Speyer to establish a press and foster printing within the Venetian Republic' (Kostylo, 2010, p. 23). In 1474 the Venetian Republic passed a decree that protected during ten years 'any new and ingenious device in this City' and in 1624 the English Statute of Monopolies63 'crystallized the pronouncements of the common law courts concerning the use by the English Crown of its prerogative power to grant monopolies in business [...] for "any manner of new manufactures within this realm"' (Drahos, 2010, p. 91). These initiatives were followed by diverse patent statutes in Europe: France 1791, Austria 1810, Russia 1812, Prussia 1815, Belgium and the Netherlands 1817, Spain 1820, Bavaria 1825, Sweden 1834, Wurtemburg 1836, Portugal 1837, Saxonia 1843 (Drahos, 2010, pp. 91-92), although statutes were previously anticipated by customary law.64 Finally, in order to avoid the territorial application of the patents and to obtain international recognition, in 1883 the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property was signed.

Despite the expansion of patent statutes, Sam Ricketson narrates how the patents 'could be seen as restraints on the development of a free market economy, particularly in those European countries that were commencing to industrialize'. This understanding of patents produced their abolition in the Netherlands in 1869, a country which repealed its patent law, and a strong contestation in Switzerland and Germany (Ricketson, 2015, § [1.07]-[1.08]), beginning discussions which still continue today related to the foundations of patents (Anderfelt, 1971, pp. 50-58), the malfunctioning of the procedure to obtain one65, the endangering of innovation or their inefficiency (Jaffe & Lerner, 2004), notwithstanding the danger to innovation caused by the existence of a myriad of 'patent assertion entities' (PAEs), also called 'patent monetization entities' or better known after their colloquial name 'patent trolls' (Lallement, 2017, p. 101; Tucker, 2011).

Definition and regulation

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) definition,

'a patent is a document issued upon application by a government office (or a regional office acting for several countries), which describes an invention and creates a legal situation in which the patented invention can normally only be exploited (manufactured, used, sold, imported) with the authorization of the owner of the patent. "Invention" means a solution to a specific problem in the field of technology. An invention may relate to a product or a process. The protection conferred by the patent is limited in time (generally 20 years)'. (WIPO, 2008, p. 17).

Although patents are referred to as 'monopolies', this term is not exact because they do not confer the inventor the right 'to make, use or sell anything'. A patent gives the owner of the patented invention the right to 'exclude others from commercially exploiting his invention' (ibidem). In the same sense, the EPO asserts that 'Patents confer the right to prevent third parties from exploiting an invention for commercial purposes without authorisation' (European Patent Office, 2016, p. 6). It is the patentee who will have to take care of the action upon the infringement of his rights so as to exclude others.

Patents are regulated in articles 27 to 34 of the TRIPS agreement, which establish an applicable default rule, 'patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application', and provides the possibility of the signatories to exclude from patentability:

-

Inventions which commercial exploitation could contravene public order or morality.

-

Diagnostic, therapeutic and surgical methods for the treatment of humans or animals;

-

Plants and animals other than micro-organisms, and essentially biological processes for the production of plants or animals other than non-biological and microbiological processes.

In Europe, a group of contracting states66 signed the European Patent Convention (EPC), which entered into force on 13 December 2007. According to article 52 of the EPC:

(1) European patents shall be granted for any inventions, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application.

(2) The following in particular shall not be regarded as inventions within the meaning of paragraph 1:

a. discoveries, scientific theories and mathematical methods;

b. aesthetic creations;

c. schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers;

d. presentations of information.

'The EPC has established a single European procedure for the grant of patents on the basis of a single application and created a uniform body of substantive patent law designed to provide easier, cheaper and stronger protection for inventions in the contracting states' (European Patent Office, 2020a, p. 10). Due to this Convention, a patentee may file a single application and obtain the registration of an invention in the countries designated by the patent candidate (idem, pp. 12-14). It is not a single patent, but a bundle of them, which although its advantages 'has the disadvantage that infringement and/or invalidation procedures must be conducted separately in the individual Member States' (Kur & Dreier, 2013, p. 88). However, continue these authors, 'obtaining patent protection for the major EU countries such as the UK, France, Germany and perhaps Italy or Spain, may be sufficient to secure de facto EU-wide protection'.

A final possibility for filing a patent is using the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), which was signed at Washington in June 1970, today with 153 contracting states. According to article 2, item (ix), 'references to a "patent" shall be construed as references to national patents and regional patents'. Inventors who wish to file their application in several countries may use the proceedings of this Treaty and issue their petition via WIPO's International Bureau or through a national patent office. This does not mean the applicant will obtain a single patent for all the countries but only in the ones where the patent is asked for.

In addition to the above, currently, a Unitary Patent for protection in all the EU territory is under development. The legal norms that regulate it are the following ones:

-

Regulation (EU) No 1257/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2012 implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of unitary patent protection.67

-

Council Regulation (EU) No 1260/2012 of 17 December 2012 implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of unitary patent protection with regard to the applicable translation arrangements.68

-

Agreement on a Unified Patent Court,69 not yet enforceable as ratification by signatories is pending.

Requirements for patentability and disclosure of the invention

For an invention to be eligible for patent protection it must follow certain requirements: it must be industrially applicable (useful), new (novel), it must exhibit a sufficient 'inventive step' (be non-obvious) and the disclosure of the invention in the patent application must meet certain standards (WIPO, 2008, p. 17). As per paragraph 1 of article 52 of the EPC: 'European patents shall be granted for any inventions, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are susceptible of industrial application'.

The challenges that are faced by the patent offices in order to review the applications are increasingly more complex. According to EPO, 'Prior art is the starting point for searching any patent application. EPO examiners have access to the world's most extensive prior art collection, which includes 1.5 billion technical records in 182 databases' (European Patent Office, 2020b, p. 14), notwithstanding the 120 million patent documents, 4.1 million standards documents and non-patent literature (idem, pp. 15-16). The existence of prior art will be an issue for granting the patent. Therefore, patents and publications about the patents may coexist, but the patent application must be prior in time than the publication, as to accomplish the requirement of the novelty.